Johannes’ brother Henry built the Henry Fite House.

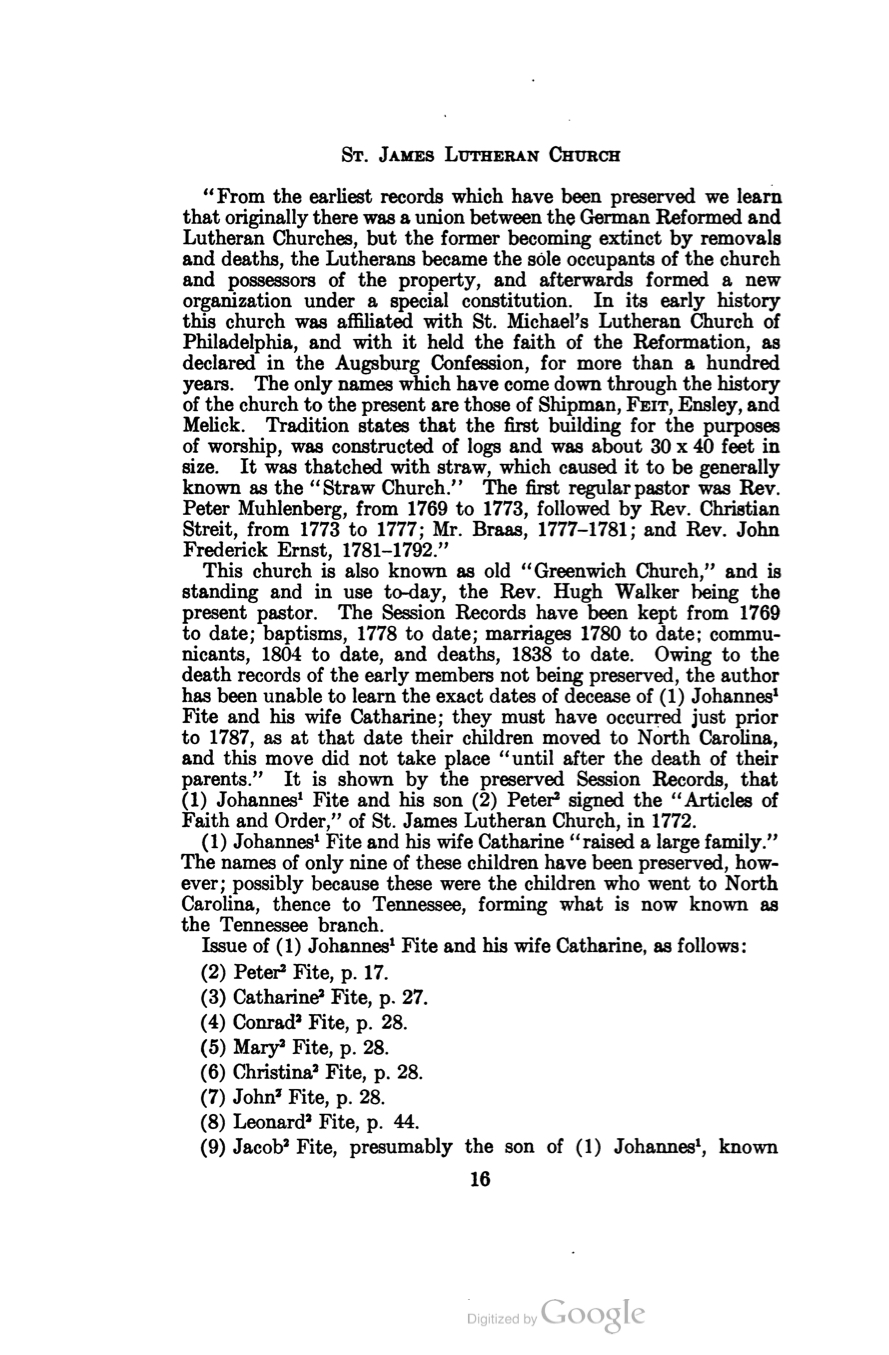

Henry Fite House:

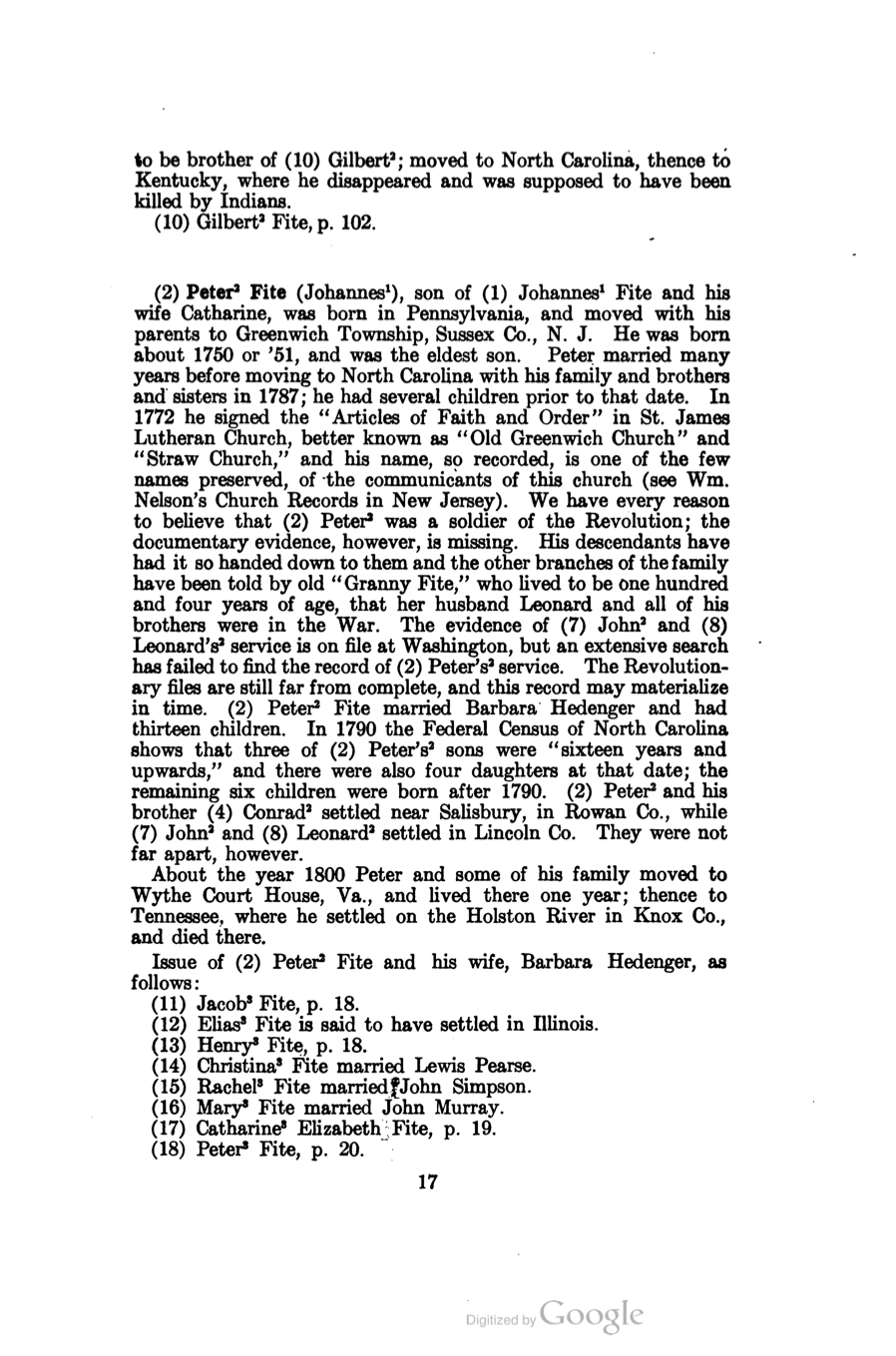

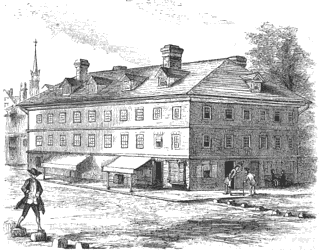

The “Henry Fite House”, located on West Baltimore Street (then known as Market Street), between South Sharp and North Liberty Streets (also later known as Hopkins Place), in Baltimore, Maryland, was the meeting site of the Second Continental Congress from December 20, 1776 until February 22, 1777.[1] Built as an inn and tavern around 1770 in the Georgian architectural style in red brick with white wood trim by Henry Fite (1722–1789), the building became known as “Congress Hall” when it briefly served as the new nation’s seat of government in 1776–77. Later, following the Revolutionary War, it became known locally as “Old Congress Hall”. The structure was destroyed during the February 7–8, 1904 Great Baltimore Fire, which started nearby.[2]

Nation’s capital:

The Second Continental Congress moved from Philadelphia to Baltimore in the winter of 1776 to avoid capture by British forces, who were advancing on Philadelphia, the new American capital city, during the New York and New Jersey campaign. As the largest building then in forty-seven-year-old Baltimore Town, Henry Fite’s six year old tavern provided a comfortable location of sufficient size for the Congress to meet; its site at the western edge of town was beyond easy reach of the British Royal Navy‘s ships and artillery should they try to sail up the Harbor and the Patapsco River to shell the town. A visitor described the tavern as a “three-story and attic brick house, of about 92 feet front on Market Street, by about 50 or 55 feet depth on the side streets, with cellar under the whole; having 14 rooms, exclusive of kitchen, wash-house and other out-buildings, including a stable for 30 horses.”[2][3]

Thus, Baltimore became the nation’s capital for a two-month period. While meeting here in Maryland on December 27, 1776, the Continental Congress conferred upon General George Washington, (1732–1799), “extraordinary powers for the conduct of the Revolutionary War,” a stirring vote of confidence, now a year and-a-half after having commissioned him as head of the newly organized Continental Army, following a series of defeats and retreats since the Virginian assumed command in June 1775, when the Army recruited from local militia surrounded the British in a siege at Boston after the opening skirmishes in April at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts followed by the June British attack at Breed’s and Bunker Hills across the Charles River from Boston.[4][2]

In her 1907 biography of the Fite family, descendent Elizabeth Fite corrected earlier historians who mistakenly reported Jacob Fite as the owner of the house. She explained that while Henry’s son, Jacob, lived in the house, he was a child when the building was occupied by Congress and never actually owned the building. After Henry died on October 25, 1789, his estate was distributed among his seven surviving children; the “Henry Fite House” became the property of his eldest daughter, Elizabeth, and her husband, George Reinicker.[2]

George Peabody:

Philanthropist and international financier George Peabody (1795–1869), of South Danvers (later Peabody), Massachusetts and New York City, moved to Baltimore in 1816. The “Henry Fite House” served as his home and office during the next 20 years in the 1820s and 30s, where he directed his growing wide-ranging business, financial and investment empire, which by mid-century had made him the richest man in America.[5] He later endowed the Peabody Institute in 1857, which opened nine years later with the adjoining Library in 1878. Along with the additional educational, cultural and civic programs in the mid-1860s, the Institute and Conservatory were to be built across from the Washington Monument on the Circle at North Charles and East Monument Streets (also known as Washington Place and Mount Vernon Place) in the northern city neighborhood of Mount Vernon-Belvedere formerly known as “Howard’s Woods” on the “Belvidere” estate and mansion of Revolutionary War commander of the Maryland Line in the Continental Army, Col. John Eager Howard (1752-1827) who donated the land. Later during the decades following his 1827 death, his sons and family cut up and divided the estate building large elaborate substantial townhouses on a grid of streets including Peabody’s Institute added north of original colonial era in Baltimore Town.

Peabody left Baltimore for New York City and later London in 1837, as more and more of his international financial and business affairs consumed his time. His most famous return to the city was in 1866 (three years before his death) to address the large crowd of Baltimoreans including Baltimore City Public School children gathered on the front steps of his new Institute when it was finally dedicated in an elaborate ceremony after a long interval, interrupted by the Civil War.

George Peabody (/ˈpiːbədi/ PEE-bə-dee;[2] February 18, 1795 – November 4, 1869) was an American financier and philanthropist. He is widely regarded as the father of modern philanthropy.

Born into a poor family in Massachusetts, Peabody went into business in dry goods and later into banking. In 1837 he moved to London (which was then the capital of world finance) where he became the most noted American banker and helped to establish the young country’s international credit. Having no son of his own to whom he could pass on his business, Peabody took on Junius Spencer Morgan as a partner in 1854 and their joint business would go on to become J.P. Morgan & Co. after Peabody’s 1864 retirement.

Royal Farms Arena:

The former location of the “Henry Fite House” is currently occupied by the Royal Farms Arena, originally known as the Baltimore Civic Center and from 2003-2013 1st Mariner Arena. Built in 1961–62 in the western downtown area, with a civic auditorium, arena, convention hall and exhibition galleries, the building became a center of Baltimore’s sports and entertainment life. It covers the city block bounded by West Baltimore Street (north), Hopkins Place (east), Howard Street (west) and West Lombard Street (south).

Memorial tablet:

The Maryland Society of the Sons of the American Revolution placed a large, elaborate, polished bronze memorial tablet in front of the “Henry Fite House” on February 22, 1894, describing the building’s brief service to the nation. An inscription on the tablet proclaimed to visitors: “On this site stood Old Congress Hall, in which the Continental Congress met”. Ten years later, only the memorial tablet remained on the corner of the smoking ruins after the Great Fire on February 7–8, 1904, which devastated most of downtown Baltimore and the waterfront.[2][3]

When the Civic Center (now the Royal Farms Arena) was built on the site, the bronze tablet of 1894 was preserved and mounted on the outside wall facing Hopkins Place, near the northeast corner of the building. During a later remodel, the plaque was moved inside the new glass-enclosed lobby.

See also:

- Former national capitals

- Maryland in the American Revolution

- Timeline of Baltimore history

- History of Baltimore

- History of Maryland

References:

- ^ “Henry Fite’s House, Baltimore”. U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Elizabeth Mitchell Stephenson Fite (1907). The biographical and genealogical records of the Fite families in the United States. The Greenwich Printing Company, New York. pp. 106–112. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “A Tablet for Congress Hall: Baltimore’s Historic Building to be Appropriately Marked” (PDF). New York Times. February 21, 1894. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ John Montgomery Gambrill (1903). Leading events of Maryland history. Ginn & Company, Boston. p. 119. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ “George Peabody: Founder of the Peabody Institute”. Maryland State Archives. November 13, 2001. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

Henry Fite House

Old Congress Hall Baltimore, Maryland

December 20, 1776 to February 27, 1777

No Longer Standing

201 W Baltimore St, Baltimore, MD 21201

On February 22, 1894, the Sons of the American Revolution placed a large, elaborate, polished bronze memorial tablet in front of the “Henry Fite House.” The plaque described the building’s two month service to the nation proclaiming: “On this site stood Old Congress Hall, in which the Continental Congress met”. Above the plate containing the picture and inscription, is an ornamental cornice, with an eagle with outstretched wings on each corner, and a supported scroll-work, surmounted by a star in the center. The sides of the tablets are rounded. On one of these rounded sides are the names of seven of the original thirteen states — Maryland, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Delaware, New York, Rhode Island and Connecticut — with a star between each; and on the other side the names of the other six: New Hampshire, New Jersey, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. Shields decorate the lower corner

On February 7–8, 1904, the Old Congress Hall was consumed by the Great Baltimore Fire. Only the memorial tablet remained on the corner of the smoking ruins Today, the 1st Mariner Arena located at 201 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 stands on the historic site of Old Congress Hall.

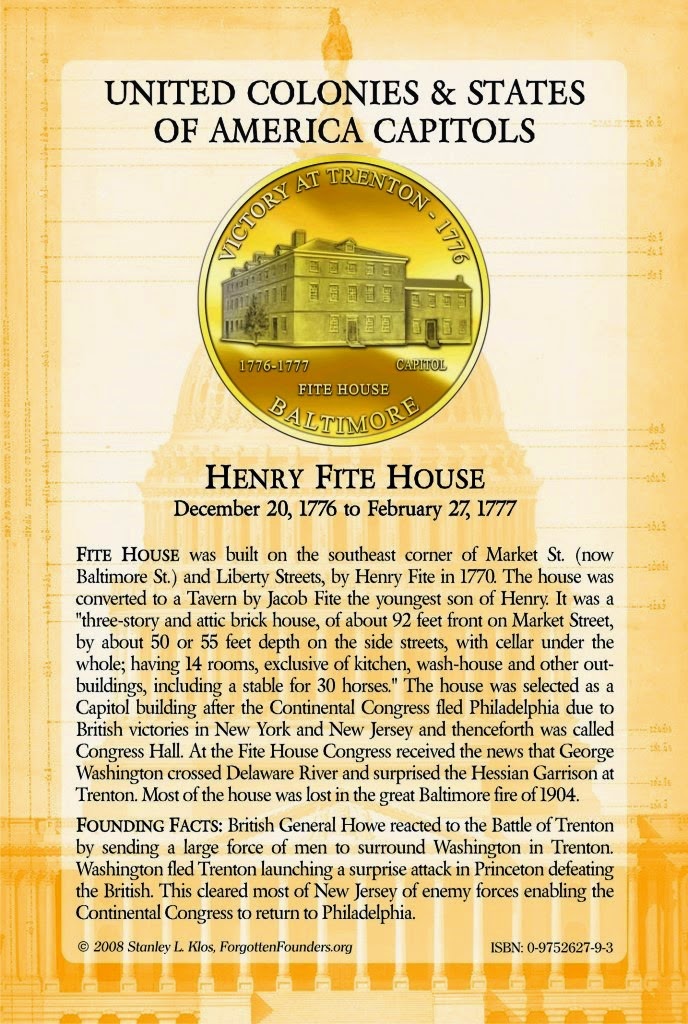

[1] Mary Katherine Goddard (June 16, 1738 – August 12, 1816) was an early American publisher and the first American postmistress. She was the first to print the Declaration of Independence with the names of the signatories. She served as Baltimore’s postmaster for 14 years (1775-1789).

| U.S. Continental Congress President John Hancock |

United States Continental Congress Fite House Legislation:

January 1, 1777 Appoints Benjamin Franklin commissioner to the Court of Spain. January 3 Directs General Washington to investigate and protest General Howe’s treatment of Congressman Richard Stockton and other American prisoners. January 6 Denounces Howe’s treatment of General Charles Lee and threatens retaliation against prisoners falling into American hands. January 8 Authorizes posting continental garrisons for the defense of western Virginia and financing Massachusetts’ expedition against Fort Cumberland, Nova Scotia. January 9 Dismisses John Morgan, director general of military hospitals, and Samuel Stringer, director of the northern department hospital. January 14 Adopts proposals to bolster Continental money and recommends state taxation to meet state quotas. January 16 Proposes appointment of a commissary for American prisoners held by the British; orders inquiry into British and Hessian depredations in New York and New Jersey. January 18 Orders distribution of authenticated copies of the Declaration of Independence containing the names of signers:

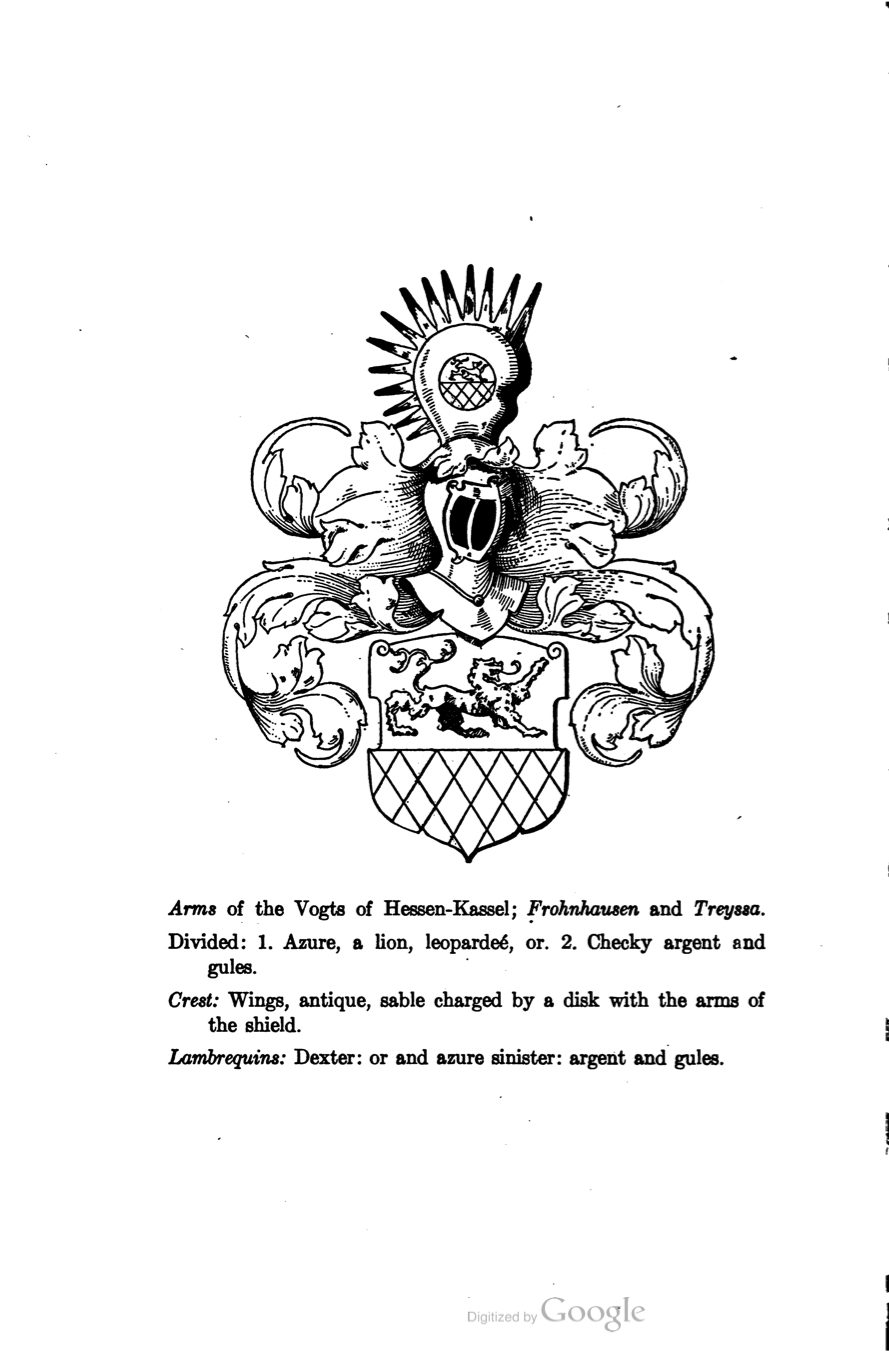

(Johannes and Henry were Hessian’s, from Hessen-Kassel.) On January 16th at the Fite House, they were discussing Hessians New York and New Jersey. Johannes Vogt gave supplies to General Greene who was fighting in New York and New Jersey Campaigns… Johannes Fite’s (Vogt’s) son Leonard Fite was fighting in the revolution… He was living in New Jersey… It is pretty possible that they were fighting against their own Hessian (Countrymen) I image that this was a very deeply moving circumstance to be in.

Delaware • George Read • Caesar Rodney • Thomas McKean [not present on Goddard Broadside] Pennsylvania • George Clymer • Benjamin Franklin • Robert Morris • John Morton • Benjamin Rush • George Ross • James Smith • James Wilson • George Taylor Massachusetts • John Adams • Samuel Adams • John Hancock • Robert Treat Paine • Elbridge Gerry New Hampshire • Josiah Bartlett • William Whipple • Matthew Thornton Rhode Island • Stephen Hopkins • William Ellery New York • Lewis Morris • Philip Livingston • Francis Lewis • William Floyd Georgia • Button Gwinnett • Lyman Hall • George Walton Virginia • RichardHenry Lee • Francis Lightfoot Lee • Carter Braxton • Benjamin Harrison • ThomasJefferson • George Wythe • Thomas Nelson, Jr. North Carolina • William Hooper • John Penn • Joseph Hewes South Carolina • Edward Rutledge • Arthur Middleton • Thomas Lynch, Jr. • Thomas Heyward, Jr. New Jersey • Abraham Clark • John Hart • Francis Hopkinson • Richard Stockton • John Witherspoon Connecticut • Samuel Huntington • Roger Sherman • William Williams • Oliver Wolcott Maryland • Charles Carroll • Samuel Chase • Thomas Stone • William Paca,

January 24 Provides money for holding an Indian treaty at Easton. Pa. January 28 Appoints committee to study the condition of Georgia. January 29 Directs Joseph Trumbull to conduct an inquiry into activities of his deputy commissary Carpenter Wharton. January 30 Creates standing committee on appeals from state admiralty courts.

February 1 Orders measures for suppressing insurrection in Worcester and Somerset counties, Maryland. February 5 Orders measures for obtaining troops from the Carolinas; instructs Secret Committee on procuring supplies from France. February 6 Directs measures for the defense of Georgia and for securing the friendship of the southern Indians. February 10 Recommends temporary embargo in response to British naval “infestation” of Chesapeake Bay. February 12 Recommends inoculation of Continental troops for smallpox. February 15 Endorses the substance of the recommendations adopted at the December-January New England Conference and recommends the convening of two similar conferences in the middle and southern states. February 17 Endorses General Schuyler’s efforts to retain the friend ship of the Six Nations. February 18 Directs General George Washington to conduct inquiry into military abilities of foreign officers.February 19 Elects five major generals. February 21 Rejects General Lee’s request for a congressional delegation to meet with him to consider British peace overtures; elects 10 brigadier generals. February 22 resolves to borrow $13 million in loan office certificates. February 25 Adopts measures to curb desertion. February 26 Raises interest on loan office certificates from 4% to 6%. February 27 Cautions Virginia on expeditions against the Indians: adjourns to Philadelphia, to reconvene on March 5.

Capitals of the United States and Colonies of America

| Philadelphia | Sept. 5, 1774 to Oct. 24, 1774 | City Tavern & Carpenter’s Hall |

| Philadelphia | May 10, 1775 to Dec. 12, 1776 | Pennsylvania State House |

| Baltimore | Dec. 20, 1776 to Feb. 27, 1777 | Henry Fite’s House |

| Philadelphia | March 4, 1777 to Sept. 18, 1777 | Pennsylvania State House |

| Lancaster | September 27, 1777 | Lancaster Court House |

| York | Sept. 30, 1777 to June 27, 1778 | York-town Court House |

| Philadelphia | July 2, 1778 to June 21, 1783 | College Hall – PA State House |

| Princeton | June 30, 1783 to Nov. 4, 1783 | Nassau Hall |

| Annapolis | Nov. 26, 1783 to Aug. 19, 1784 | Maryland, State House |

| Trenton | Nov. 1, 1784 to Dec. 24, 1784 | French Arms Tavern |

| New York City | Jan. 11, 1785 to Nov. 13, 1788 | New York City Hall |

| New York City | October 6, 1788 to March 3,1789 | Walter Livingston House |

| New York City | March 3,1789 to August 12, 1790 | Federal Hall |

| Philadelphia | December 6,1790 to May 14, 1800 | Congress Hall |

| Washington DC | November 17,1800 to Present | Five US Capitols |

https://bearings.earlybaltimore.org/

As we can see from this 19th-century photograph of St. Peter’s, the BEARINGS group did a remarkable job of creating an accurate version of the building, based on the descriptive materials (i.e. photographs) that it had at its disposal. Well done. The truly astounding part about seeing St. Peter’s visualized on a 3-D map, however, is noticing just how close it was to the Henry Fite House, a.k.a. “Congress Hall,” where Continental Congress met from December 20th 1776 through February 27th 1777, when Baltimore Town was the Capital of the fledgling United States of America and the Fite House was its capitol. An all-too-unknown fact, if you ask me—and one that puts Baltimore in some rather exclusive company.

Only two places served as the nation’s capital during that pivotal year of 1776. Everyone knows about Philadelphia … but what about Baltimore?! Almost no one knows that our city (née town) shared the same honor. We, as a city, ought to make a bigger deal out of that, because aside from a small plaque which sits at the bottom of a ramp on the 1st-level concourse of the Baltimore Arena (that barely anyone bothers to stop and read), I can’t think of another way in which that momentous fact is celebrated. We simply must figure out a way to make that common knowledge! It would boost the level of civic pride tenfold.

The engrossed parchment of the Declaration of Independence was formally enshrined in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. on December 15, 1952, where it resides to this day. From its creation in the summer of 1776 to this final move, the Declaration of Independence travelled more than might be assumed. This month, we trace the engrossed parchment’s physical locations and custodians through the first 100 years of its existence, starting and ending with Independence Hall. Stay tuned for part two (1877-today) in February!

1776

Continental Congress

Philadelphia

On July 19, 1776, the Continental Congress resolved, “That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of ‘The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,’ and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress.” Timothy Matlack likely took on this task, and on August 2nd, in the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia, the engrossed parchment was signed by the majority of the 56 delegates.

1776-1789

Continental Congress/Congress of the Confederation

Philadelphia -> Baltimore -> Philadelphia -> Lancaster -> York -> Philadelphia -> Princeton -> Annapolis -> Trenton -> New York City

It is assumed that, at this point, the engrossed parchment was entrusted to Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Continental Congress (Image above courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections). Thomson had been unanimously chosen as Secretary of the First Continental Congress on September 5, 1774. When the Second Continental Congress convened on May 10, 1775, Thomson was once again chosen as its Secretary. He stayed with the Congress as it transitioned into the Congress of the Confederation (under the Articles of Confederation), serving as secretary to the Congress for nearly 15 years, and counting among his responsibilities the care of the papers of the Congress (including the Declaration of Independence).

If the Declaration stayed with Thomson, then it is likely that it moved with the Congress, as he did. The first move came in December 1776, when the Congress evacuated Philadelphia and reconvened at the Henry Fite House in Baltimore, Maryland later that month. In January 1777, the engrossed parchment — at least the signatures at the bottom — likely served as a resource for Mary Katharine Goddard as she created her “authentic copy” of the Declaration. In March 1777, the Continental Congress returned to Independence Hall in Philadelphia, but only for a few months.

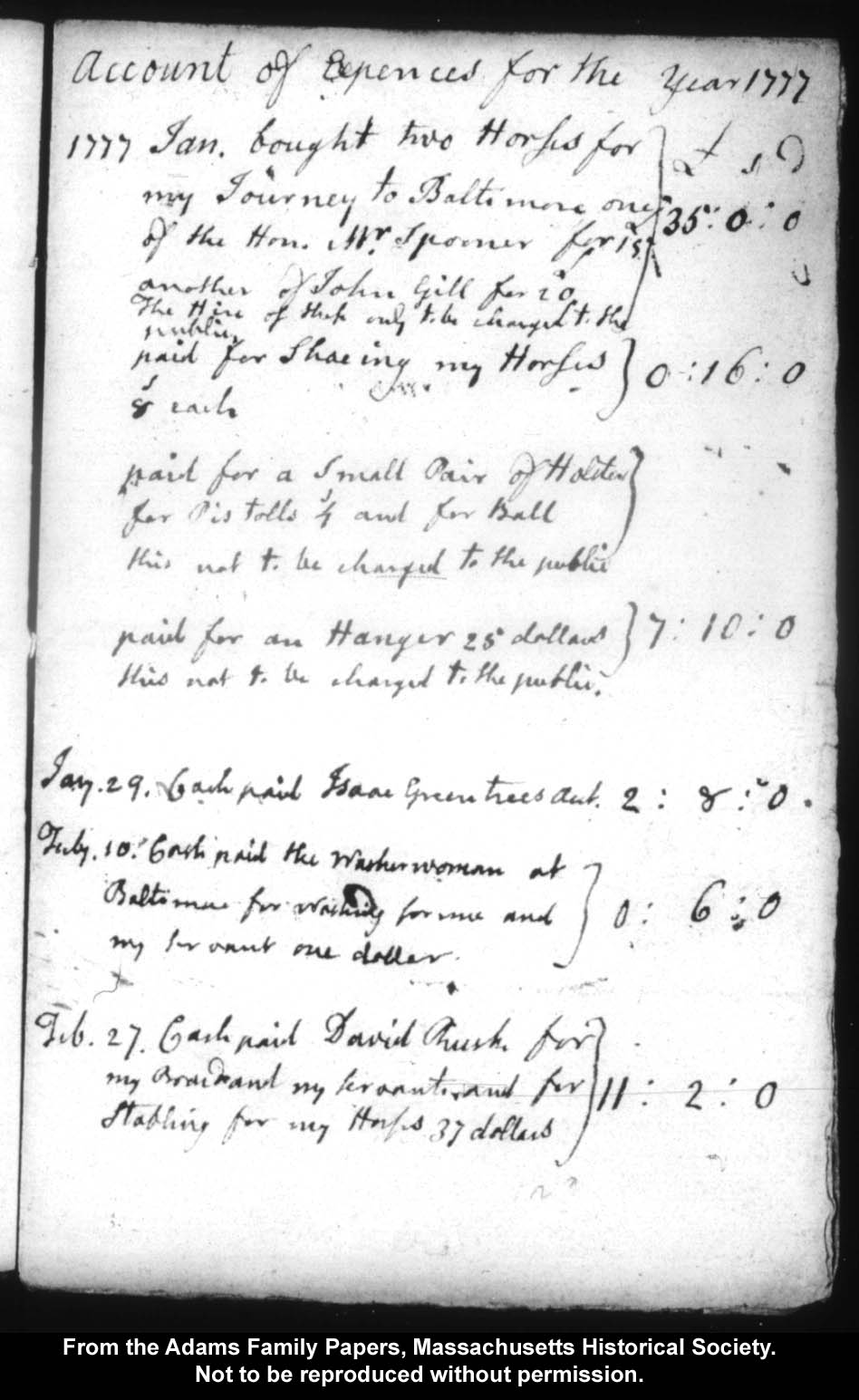

Account of Expenses for the Year, January 1777 to February 27 [i.e. 28]

| s | d | ||

| Bought two Horses for my Journey to Baltimore one of the Hon. Mr. Spooner for 15 . | 35: | 0: | 0 |

| Another of John Gill for 20 the hire of these only to be charged to the public. Paid for shoeing my horses 8s each. | 0: | 16: | 0 |

| paid for a small pair of Holsters for Pistolls 4s and for Ball. This not to be charged to the public. | |||

| Paid for an Hanger 25 dollars. This not to be charged to the public. | 7: | 10: | 0 |

| Jan. 29. Cash paid Isaac Greentrees Acct. | 2: | 8: | 0 |

| Feb.10 Cash paid the wsherwoman at Baltimore for washing for me and my servant one dollar. | 0: | 6: | 0 |

| February 27 [i.e. 28] Cash paid David Rusks for my board and my servants and for stabling for my horse, 37 dollars. | 11: | 2: | 0 |

Travel Itinerary of the Vogt Brothers:

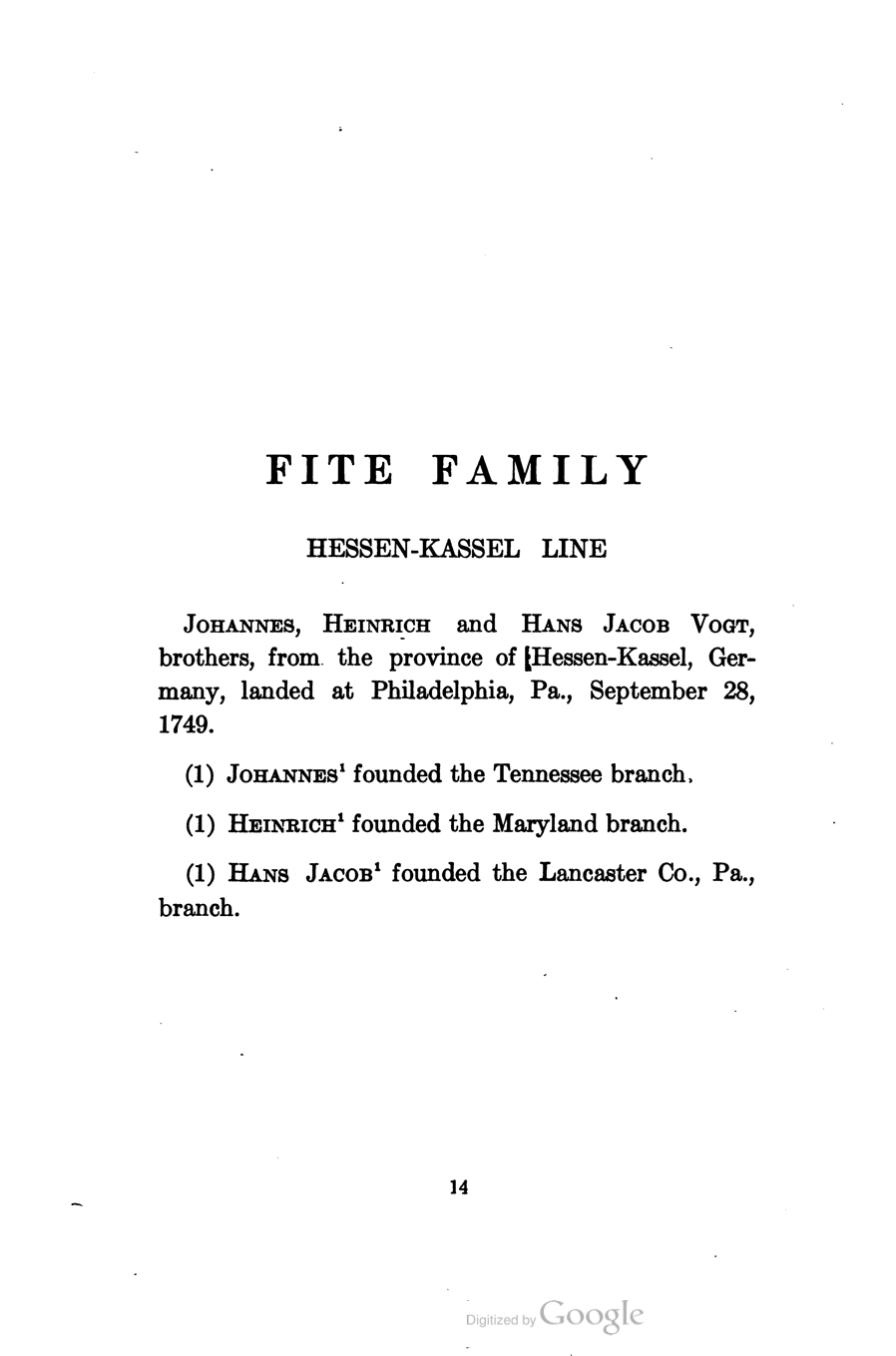

- Johannes Vogt is born and his two brothers travel to Rotterdam in 1749 to travel to America. The will leave from Rotterdam, Germany and make one stop East Cowes in the UK and then Land in Philadelphia…

2. ROTTERDAM AUG 10 1749

In “A history of New Sweden: or, The settlements on the River Delaware” By Israel Acrelius, William Morton Reynolds:

“With Rotterdam has sprung up a very profitable commerce in the transportation of German and Swiss emigrants. The ships go to South Carolina, where a cargo of rice is taken in, and duty paid to England ; after which they go to Rotterdam. Thence the people are conveyed to Philadelphia. Each person has to pay about three hundred and fifty dollars (copper coin) for the passage. Those who have no means of payment are sold to service for three, four, or five years.” In national terms, Philadelphia was certainly most important as an immigrant port in the eighteenth century. Beginning about 1717, when the Provincial Assembly ordered ship captains to submit passenger lists to officials, there were true mass migrations of Germans and of Scotch-Irish directly to Philadelphia. In 1749, for example, 22 ships with a total of 7000 immigrants from the Rhineland made the seven-week voyage to the city. In all, about 70,000 Germans landed there before the Revolution and Philadelphia also received the largest share of the over 150,000 Scotch-Irish who migrated from Ulster to the colonies. In both groups, the majority were so poor that they had come as indentured servants or as “redemptioners” who had to work off the borrowed price of their passage. Many were thus forced to stay in the city, helping to make it the largest in the colonies by the time of the Revolution.

“Thirty Thousands Names of Immigrants” by Professor Israel Daniel Rupp: Sept. 28, 1749. Foreigners from Basel, Wirtemberg, Zweibrucken, and Darmstadt, ship Ann, John Spurier, Master, from Rotterdam, last from Cowes. 242 passengers. “A history of New Sweden: or, The settlements on the River Delaware” By Israel Acrelius, William Morton Reynolds:

“With Rotterdam has sprung up a very profitable commerce in the transportation of German and Swiss emigrants. The ships go to South Carolina, where a cargo of rice is taken in, and duty paid to England ; after which they go to Rotterdam. Thence the people are conveyed to Philadelphia. Each person has to pay about three hundred and fifty dollars (copper coin) for the passage. Those who have no means of payment are sold to service for three, four, or five years.” In national terms, Philadelphia was certainly most important as an immigrant port in the eighteenth century. Beginning about 1717, when the Provincial Assembly ordered ship captains to submit passenger lists to officials, there were true mass migrations of Germans and of Scotch-Irish directly to Philadelphia. In 1749, for example, 22 ships with a total of 7000 immigrants from the Rhineland made the seven-week voyage to the city. In all, about 70,000 Germans landed there before the Revolution and Philadelphia also received the largest share of the over 150,000 Scotch-Irish who migrated from Ulster to the colonies. In both groups, the majority were so poor that they had come as indentured servants or as “redemptioners” who had to work off the borrowed price of their passage. Many were thus forced to stay in the city, helping to make it the largest in the colonies by the time of the Revolution. 7 weeks prior on Sunday… would be August, 10th 1749….Sept. 28, 1749. Foreigners from Basel, Wirtemberg,

Zweibrucken, and Darmstadt, ship Ann, John Spurier, Master, from Rotterdam, last from Cowes. 242 passengers. So Cowes must of been the only stop before landing somewhere at the Port of Philadelphia, near “Customs House, Pennsylvania.” The earliest records we have specifically relating to Cowes is the Collector to Board Letter Book dated 1749 (although there is an isolated Board to Collector book dated 1703). There are a number of general references in earlier books.

The site of the Custom House in East Cowes has been established as being south of the White Hart public house, and the site is now the access road to the Red Funnel Terminal.https://www.customscowes.co.uk/history.htm If they landed the 28th of September than it took John Spurrier, Master one week the following Sunday to Make records at Customs House, Pennsylvania.

3. EAST COWES AUG-SEPT 1749

7 weeks prior on Sunday… would be August, 10th 1749….Sept. 28, 1749. Foreigners from Basel, Wirtemberg,

Zweibrucken, and Darmstadt, ship Ann, John Spurier, Mas-

ter, from Rotterdam, last from Cowes. 242 passengers. So Cowes must of been the only stop before landing somewhere at the Port of Philadelphia, near “Customs House, Pennsylvania.” The earliest records we have specifically relating to Cowes is the Collector to Board Letter Book dated 1749 (although there is an isolated Board to Collector book dated 1703). There are a number of general references in earlier books.

The site of the Custom House in East Cowes has been established as being south of the White Hart public house, and the site is now the access road to the Red Funnel Terminal.https://www.customscowes.co.uk/history.htm If they landed the 28th of September than it took John Spurrier, Mas-

ter one week the following Sunday to Make records at Customs House, Pennsylvania.

4. CUSTOMS HOUSE OCT 5 1749

7 weeks prior on Sunday… would be August, 10th 1749….Sept. 28, 1749. Foreigners from Basel, Wirtemberg,

Zweibrucken, and Darmstadt, ship Ann, John Spurier, Mas-

ter, from Rotterdam, last from Cowes. 242 passengers. So Cowes must of been the only stop before landing somewhere at the Port of Philadelphia, near “Customs House, Pennsylvania.” So Cowes must of been the only stop before landing somewhere at the Port of Philadelphia, near “Customs House, Pennsylvania.” The earliest records we have specifically relating to Cowes is the Collector to Board Letter Book dated 1749 (although there is an isolated Board to Collector book dated 1703). There are a number of general references in earlier books.

The site of the Custom House in East Cowes has been established as being south of the White Hart public house, and the site is now the access road to the Red Funnel Terminal.https://www.customscowes.co.uk/history.htm If they landed the 28th of September than it took John Spurrier, Mas-

ter one week the following Sunday to Make records at Customs House, Pennsylvania.on October 5, 1749… I have the news article in the email thread.

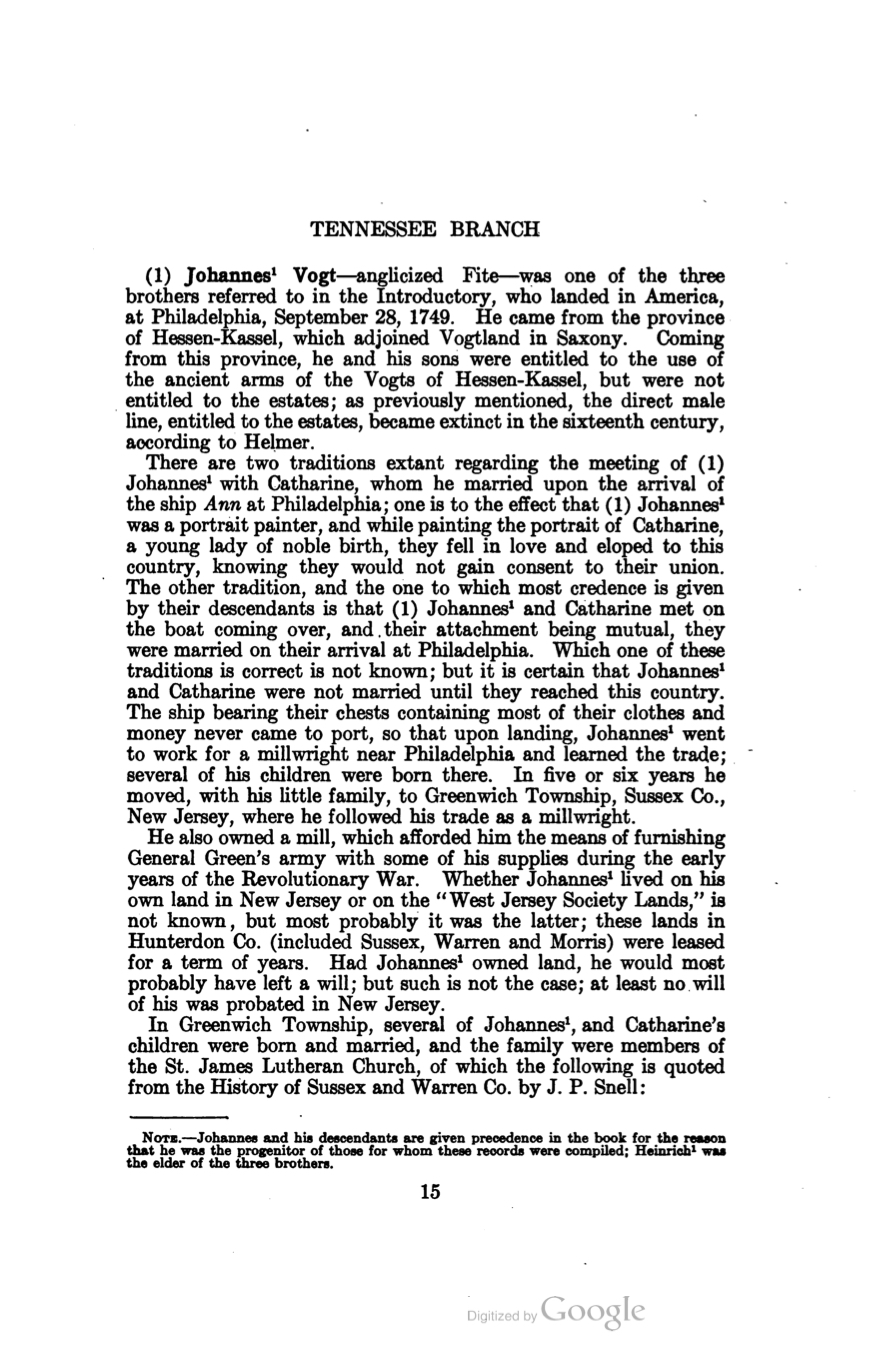

Johannes “John” Fite

| BIRTH | 1714Hessen, Germany |

|---|---|

| DEATH | Jun 1784 (aged 69–70)Sussex County, New Jersey, USA |

| BURIAL | Saint James Lutheran Cemetery Greenwich Township, Warren County, New Jersey, USA |

| MEMORIAL ID | 8009759 · View Source |

If he attended this church and is buried here in Sussex County… This could suggest that he was in Sussex and not Morris county…. I think that that is irrelevant to the story I am writing cause Morris borders Sussex… and Lewis Morris can still have a happenstance with Johannes Fite (Vogt) and Leonard Fite.